This was particularly the case in his later years. When all else failed, he would create solo works for himself, most of which weren’t notated.” As Mary Jane Leach comments: “He had a habit of situational writing, using whatever resources were available. But if Eastman sought the one in the many, he also worked with the many in the one – himself. This queerness in turn links to the utopian social vision that suffuses much of Eastman’s work.

“There is something very homosexual about using ‘multiple instruments of the same kind,’” quips Malik Gaines. Finally, as Eastman faded from the music scene in years of homelessness and addiction, there were the more fugitive works of the mid-late 1980s, sparser pieces, often designed for performance by Eastman himself, on piano or with voice, which condense, crystallize, and fracture in equal measure.Įastman wrote a significant number of works for multiples of the same instrument – ten cellos, four pianos, seven trumpets.

Julius eastman series#

Moving to New York, Eastman turned to the more driving and intense sounds of his best-known pieces, such as the 1979 N- Series ( Gay Guerrilla, Evil Nigger, and Crazy Nigger), or the multiple cellos of The Holy Presence of Joan D’Arc(1981), which emphasize darker tones, complex unison and phase playing, and an increasingly ghostly, intense emotional tenor.

Julius eastman full#

During this time, Eastman also produced one of his most accessible works, the joyous Stay On It (1973) which stretches out the buoyant energy of the three-minute pop song over a full twenty minutes. Amongst such pieces, recordings have recently surfaced of Macle (1971), in which voices shift in pitch like the droning tones of bees, and Creation (1973), where there are stuttering piano figures, more mellifluous flute lines, percussive rings and taps, and ghostly quotations of popular songs like “The Girl from Ipanema.” “Show us, show us … the pure tit,” proclaims Eastman, setting off a burst of cowboy harmonica in protest. Ensemble, of which he was a member, to destabilize performance expectations and environment through spoken text, unconventional instrumentation, exaggerated theatricality, parody, and irony, while laying the ground for the peculiar combination of fragility and grandiose strength that would characterize the sound of his mature works. Ensemble or whichever performers were at hand.įrom 1968 to 1975, Eastman worked in Buffalo with the S.E.M. He was, above all, a working musician, whose compositional methods incorporated indeterminacy, improvisation, and adaptation to on-the-fly situations, and his pieces were often written for indeterminate forces, whether that would be the unusual instrumentation of the S.E.M.

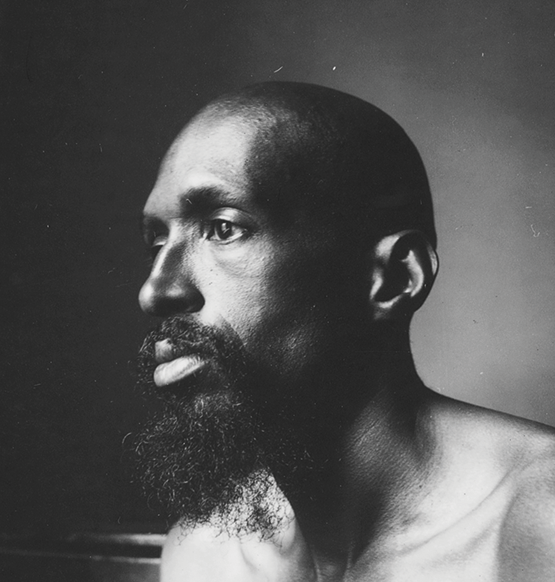

Yet, as Eastman’s 1979 essay suggests, his entire aesthetic challenges the very notion of compositional authority and the structures of concert programming involved in today’s revival of interest in his work. Since then, one more book has appeared, from Berlin-based gallery Savvy Contemporary, and Eastman’s pieces have featured on programs around the world, including a festival at Munich’s Lenbachhaus, with a final concert on March 14, 2022. The same year, the London Contemporary Music Festival put on the first major festival of his music, followed by the “ That Which is Fundamental” exhibition and concert series in 2017. In 2016, Mary Jane Leach and Renée Levine Packer co-edited Gay Guerrilla, a series of essays on Eastman’s work which revealed fresh facets of his art. From remaining virtually unheard in the wake of his tragically early death in 1990, his works are now regularly performed across Europe and America. Since the release of the box set Unjust Malaisein 2005, Eastman’s own reputation as a composer has undergone a significant revival. To remedy this, Eastman suggested, the composer must “reassert him/herself as an active part of the musical community,” becoming a “total musician, not only a composer. Since the days of church organists, court composers, and itinerant troubadours, Eastman argues, there’s been a split between solo performers, star conductors, and the composers now rendered lonely “queen bees” cut from the collective process of music-making. The composer Julius Eastman makes this point in his short, provocative essay “The Composer as Weakling” (1979), tracing a brief but ambitious history of Western “classical music” to suggest a radical shift in how we view the relation between composing and performance. “Music was born in 1700, lived a full life until 1850 at which time music caught an incurable disease and finally died in 1900.” At least, so one might surmise, given the present state of things.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)